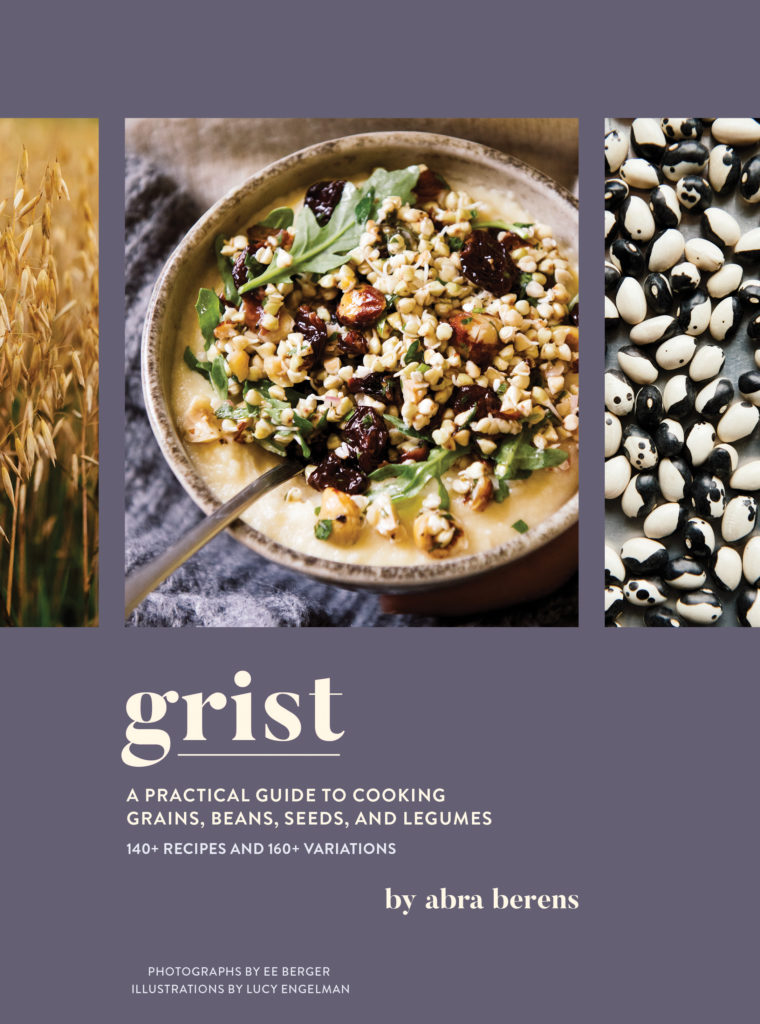

Excerpted from Grist: A Practical Guide to Cooking Grains, Beans, Seeds, and Legumes by Abra Berens with

permission from Chronicle Books, 2021. Photographs © EE Berger.

Wild rice is top of mind when thinking about traditional foods of the Great Lakes region. Feeding into the freshwater basin are vast networks of inland lakes. These lakes are the wellspring for wild rice, which isn’t technically a rice at all but an indigenous aquatic grass. Truly wild rice, as you’ll read in the interview, is hand-harvested and unique to the season, the paddy in which it is grown, and the hands that take it from lake to table.

Historically, those hands belonged to members of the First Nations, Ojibwe in my region. Images of wild rice knocked into birch canoes and parched over large fires in traditional woven baskets not only are romantic but also represent a long-held revenue source for tribes. We all have to come to terms with the fact that we live on occupied land. Buying true wild rice from Indigenous harvesters is maybe the babiest of baby steps, but I hope that it is your first on a path toward celebrating Indigenous culture and foodways. I hope that celebration then leads to further support, emotional and monetary, so that voices like Hillel Echo-Hawk, Brit Reed, Kristina Stanley, and Sean Sherman continue to drive the conversation.

NOTES

BOTANICAL NAME: Zizania palustris (of the Northern Midwest) and Zizania aquatica (of New York and Florida)

PLACE OF ORIGIN: Northern North America

TOP GLOBAL PRODUCERS: United States, Canada, Hungary, Australia, and China

GLUTEN FREE: Yes

PROTEIN CONTENT: 4 percent

TO SOAK OR NOT TO SOAK (THAT IS ALWAYS THE QUESTION): Soaking decreases cooking time and encourages the grains to pop open, but you can cook unsoaked wild rice. Wild harvested rice will cook in about half the time of cultivated wild rice.

BASIC WATER:GRAIN RATIO FOR STEWING: 6:1 (4:1 if soaked)

AVERAGE BOILING TIME: Wild harvested rice, soaked—25 minutes, unsoaked—50 minutes

YIELD RATIO AFTER COOKING: 1:2

SIGNS OF DONENESS: Grains will pop open, exposing the cream-colored inside.

FARMER PROFILE: LARRY GATES

Larry Gates is a wild rice forager in Cass Lake, Minnesota. He produces wild rice for retail and restaurant customers. I was put in touch with him via my friend, chef and former Minnesotan Paul Berglund. I wanted to talk with Mr. Gates to learn more about the difference between commercial foraging and farming, as well as the current state of wild rice production. He spoke with me in early March 2020.

Abra Berens: Can you tell me about the life cycle of wild rice—how it grows, when it’s harvested, and so on?

Larry Gates: Well, let’s start with the harvest. Rice is usually ready to harvest mid-August to mid-September. It usually takes a few weeks going from paddy to paddy and then going back again for the second flush. The rice doesn’t produce all at once, not like cultivated crops. So you go back out and keep collecting until there’s no more—usually about a month or so.

The thing that has changed the most [about foraging wild rice] is how few people are out now to harvest. It used to be big community affairs, with families going out in the boats to knock rice. Now very few people are out at any given time. With that and circling back around, time just adds up. Two people are usually harvesting together; one person moves the canoe by pushing it with a pole. Paddles don’t do much good because of the thicket of plants. The other person knocks the rice [from the flower heads] into the belly of the boat to collect it. After the final pass for collecting, the unharvested seeds fall to the water and sink to the bottom. There they lie until the weather warms in the spring, when they germinate and send up shoots. Wild rice is a grass, much closer to wheat than to Asian rice varieties. These grains can stay in the soil underwater for upward of ten years, so if there is a bad crop one year, plants will still come up the next without our intervention. Unlike cultivated wild rice (or paddy rice, as we call it), these seeds are true to the wild rice from hundreds of years ago. There’s some natural variation, but it is an ancestral crop. The stalks come up around June and then you’re just waiting. Hoping that storms don’t come through and knock ’em back. Hoping that there’s enough rain to keep off a drought. Hoping there’s not too much rain to keep the fields from germinating in the first place.

AB: What’s the difference between wild rice and paddy rice?

LG: The University [of Minnesota] started to cultivate wild rice to make it a more commercially viable crop in the early 1970s. Wild rice is a completely natural product, so it changes from year to year in quality, flavor, yield. When you cultivate something, you’re taking out the variability and making it more consistent, which is better for the businesses that sell it on a larger scale. They want it all to come on at the same time, ripen at the same time, look the same, taste the same. Wild rice is subject to the whims of the weather and the location of the plants. It tastes different from paddy to paddy; it looks different. It has its own characteristics even within one harvest. We don’t control it, which also means it’s expensive, because it takes skill to hand-harvest, and the yields can vary so much.

So when folks like Uncle Ben’s wanted to have wild rice on the shelf, they needed lower prices and a consistent product. The University set about to convert it to a more traditional row crop. Now that is displacing a lot of the natural rice fields, making it even harder to protect those wild spaces.

AB: So the cultivated or paddy rice is grown in the same places as where wild rice would grow? It

isn’t taking the place of, say, a corn or soybean field?

LG: That’s right.

AB: Hmm. And is that why there are fewer people participating in the harvest of late?

LG: I don’t know if it is a direct corollary, but you know, people used to be able to make a good living from ricing. Now it is more of a hobby for most folks.

AB: And how can people tell if they are buying paddy rice or true wild rice?

LG: Well [laughs] if it’s cheap, it isn’t wild rice. Honestly, that’s the first thing. Secondly, look at it. Cultivated wild rice is jet black and uniform down the length of the grain. Wild rice is a flecked brown that is dull or matte. Cultivated rice is shiny. Also, someone told me once that you can tell cultivated rice by boiling it with a stone. When the stone is tender, the rice is just about done.

Cultivated rice takes a lot longer to cook. And, well, I’m a Minnesotan, so I’m always going to say that Minnesota rice is the best, but if it says California on the label, it is probably cultivated.

AB: I’m from Michigan, and we have some wild rice producers up north, so let’s just say Minnesota or Michigan! Now, what do you wish non-farmers knew about your work?

LG: That what you buy matters. Wild is a special thing. It sustained life for hundreds of years. It is a regional delicacy. By buying from a small harvester or just by caring about what you’re buying, you’re saying that it is important and worth all of our time and tradition.

Excerpted from Grist: A Practical Guide to Cooking Grains, Beans, Seeds, and Legumes by Abra Berens with

permission from Chronicle Books, 2021. Photographs © EE Berger.

Grist is available for purchase here or at your local bookstore.

Abra Berens is a chef, former farmer and a writer. She is also the author of Ruffage: A practical Guide to Vegetables.

Interested in learning more about wild rice?

Check out these resources:

- Wild Rice management and Restoration, from the Keweenaw Bay Indian Community Natural Resources Department

- NOAA and Sea Grant Support to Manoomin (Wild Rice) Restoration, from the National Oceanic Atmospheric Association

- Manoomin (Wild Rice), from the Great Lakes Indian & Fish Wildlife Commission

- Mnomen (Wild Rice) – The Food That Grows on Water, from the Gun Lake Tribe

You’re Invited!

Join the Local Food Club for an exclusive book talk on Grist with author Abra Berens on January 25th.